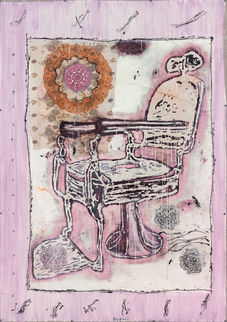

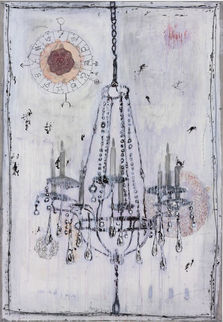

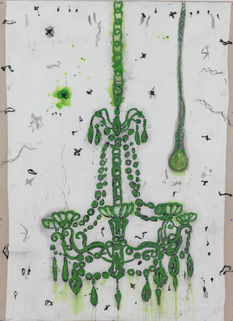

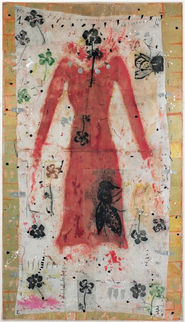

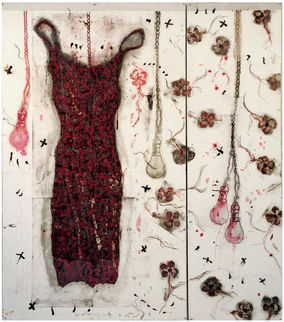

There is something strange in Didier Hagège’s dresses. They smell of sanctity and sulfur. In short, the female scent exhales in shifts of fragrances and of sensations: from seeing to smelling. Under their screening appearance, under their veil, the dresses deploy a subtle interplay of shades, of colors. However, let’s be careful about their splendid extravagances. All is not as simple as it seems. The dress is an elusive skin. It stands for a fantasized receptacle. In order to grasp and understand it, hope to touch it, we must indulge ourselves in strange choreographies.

Not only does light play, in a surprising manner, on the surface depending on our position in front of the painting, but what we had not seen at first stands out suddenly. Strange sedimentations or apparitions strike. We must not be taken in by the sole blaze of the overall appearance. We must make our way into an arrangement far more complex and elusive than it looks. If the dresses do not twirl around in the wind, a whole movement goes right through the canvasses with dynamic creativity. As a critic has put it: “Hagège is spring dressed in muslin”. Matters and materials become somersaulting hybrids. We must know how to identify scattered, disconnected elements, figurative markers here and there. They give to the whole a kind of coherent perfection made of joy and delicacy. Behind them, even if she does not appear, a woman always turns on the charm.

Hagège protests against programmed sexuality and the sportivisation of almost sexless bodies. He struggles against the pervading androgyny indicating some kind of undercover sexual repression. For him, pleasure is not confined to a sportingly mortified orgasm. Against this perversity of seeing sex everywhere so that it is nowhere and frustration operates fully, he offers a more than compensating work. To the contact of skins, Hagège substitutes encounters through a space between bodies materialized by his concealing dresses. Faced with the reification of human beings, particularly women, he proposes more than compensating healing symptoms. He reintroduces a libidinal economy into painting.

Hagège suggests a new solution to the old contradiction between subjects or objects of love or, at least, of desire. Clothes are no more stamped with suspicion. They no longer symbolize the infantile prohibition of desire. Under the dress, even if the body is elusive, it is liberated. Sexuality is decontaminated. It is no more brought down to a mere merchandize. Sensuality replaces the ideologies which in fact manipulate the mise en abyme of the body. Since such paintings rule any static state out, couldn’t a new art of desiring be seen here?

We are out of the ordinary. We no longer wail in inertia and mediocrity. Hagège adorns nothingness with a tulle crown. He invests objects and images with life. He, hence, offers soothing, relief we are badly in need of in these days of scarcity. The painter does not want to change the world but the vision we have of it. Faced with barbaric feelings and pervading terror, he offers his exercises of delicacy. His work is hence of public health. Let’s turn into companions, partners. And why not dream? “Under the cobblestones, the beach” used to be trumpeted by the 1968 anti-establishment. Under the dress is the woman, her desirable body, seems to say Hagège. We welcome this original dream. It matters little that Paradise exists or not. With his dresses (but not exclusively), the painter unveils it. This is a hedonistic cult that too few artists invite us to. It is up to us to make good use of it.

JEAN-PAUL GAVARD-PERRET